St Ethelwold’s coal era began in 1823, as local historian Meineke Cox uncovered in the early 2000’s, with Thomas Pemberton setting up shop on 30 East St Helens street. The Pemberton lineage continued until 1914 when Thomas Francis Pemberton (then living in Australia) sold the house to a tenant, retired headmistress Julia Sandys.

During this time the house worked hard and was utilitarian in design. There was a clear separation between work and life, as key architectural details reveal. For example, decorated push panels in the front two rooms of the house, an archway to signify the private side of the house and a new corridor separating the house form the coal yard.

We gain some insight into the Pembertons from the house: a warm dry place for a family bible in one of the bedrooms suggest that they were religious, like other families in Abingdon. With 18 family members in Oxfordshire, we can imagine that during the 1820-50 period the house was the scene of family gatherings during the Christian festivals. After the initial prosperity of the original Thomas Pemberton, there was emigration of the Pemberton dynasty to the small town of Colac in the state of Victoria, Australia. Eventually there was only one member of the family left in Abingdon; after the death of William Pemberton on 2 April 1888, Charles Dandridge Pemberton lived at this address until 1907 when he died intestate.

The coal business itself was, at its start, clearly prosperous given the expansive coal yard (now the garden) and grandeur of the front of the house, as a late Victorian postcard shows.

The Wilts and Berks canal was a crucial 52-mile connection between the coal fields in Somerset and Abingdon. The canal transported up to 43,642 tonnes of coal in 1837, leading us to believe that this was the primary way Pemberton got his coal. When the coal reached Abingdon, the wharf at the end of Caldecott Road was where it was bagged ready for road transport to 30 East St Helens Street by horse and cart across the iron bridge (erected in 1824 by the Wilts and Berks Canal Company). When it reached the yard at No. 30 it was prepared for local distribution. Among the potential customers were the new houses in Albert Park and the clothing factory located at the end of West Saint Helens Street.

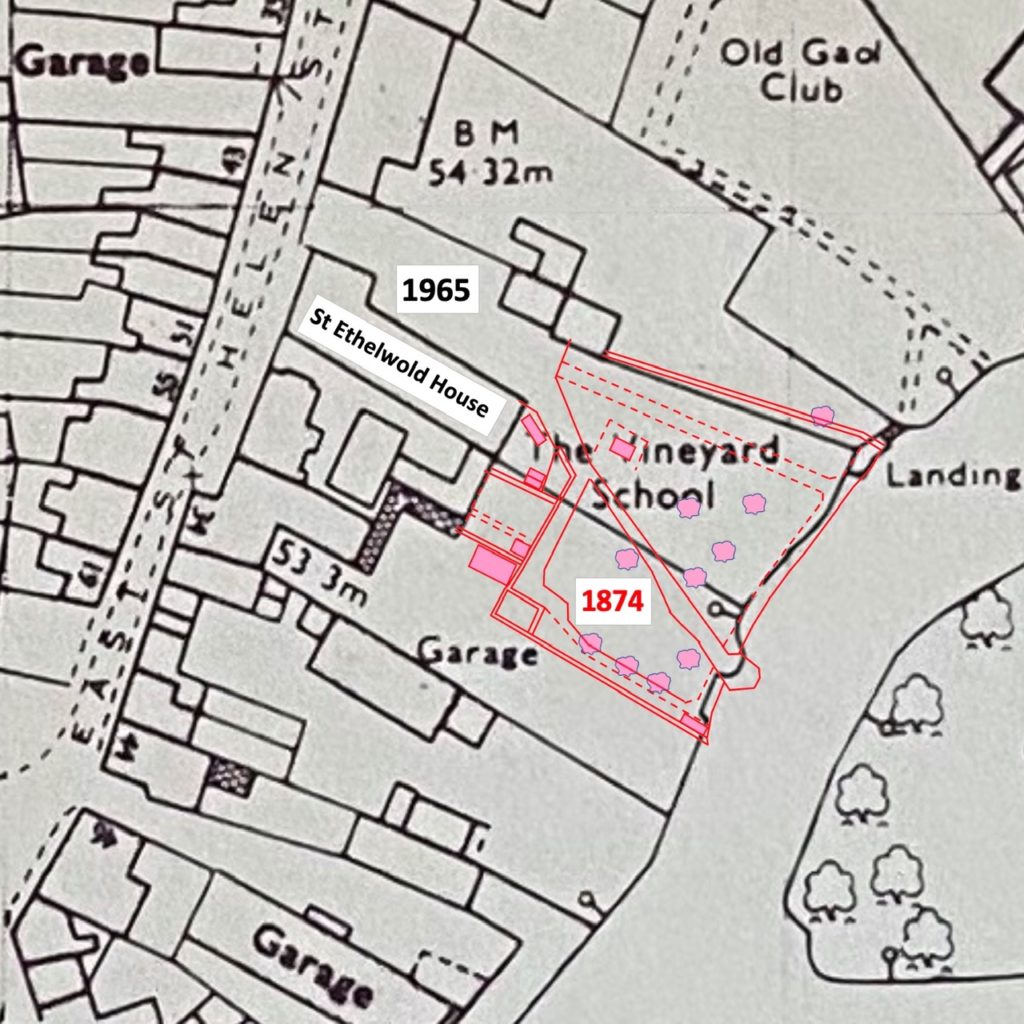

After the Great Western Railway branch line was connected up to Abingdon in 1856, whilst William Pemberton (Thomas’ son) was Mayor of Abingdon, coal would have come from the same fields around Bath, but Pemberton coal could have been sold further afield, albeit against increasing competition. Small distributors like Pemberton may have benefitted from the Britain’s smaller rail coal carts holding around 10 tonnes fully loaded. Though, more probably, the coal came the other way, from the Midlands to Abingdon via the Oxford Canal. The cost of a hundred weight (cwt) of coal fell from 2/10d to 1/10d and that would have been tough for the Pembertons. After 1874 the big yard reduced substantially to the size of the garden today.

As a result of the railway, the Wilts and Berks canal ceased to be the industrial artery it once aspired to be. It was finally decommissioned, after years of abandonment, in 1914 by Parliament. The mass exodus of Pembertons in the 1860s to Australia signifies that the coal business was no longer as profitable as it once was.

In summary, coal merchanting remained viable as the house continue to be the home of the Pemberton family for decades after the 1860s but potentially its revenue could not sustain the early grandeur.

*

This article is based on the project work of Oskar Muller who was attached from Abingdon School in July 2021.